- Home

- Schechter, Harold

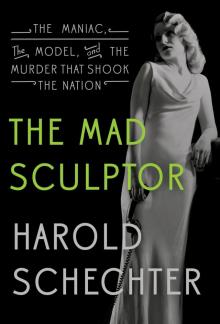

The Mad Sculptor: The Maniac, the Model, and the Murder that Shook the Nation

The Mad Sculptor: The Maniac, the Model, and the Murder that Shook the Nation Read online

Also by Harold Schechter

NONFICTION

The A to Z Encyclopedia of Serial Killers (with David Everitt)

Bestial: The Savage Trail of a True American Monster

Depraved: The Shocking True Story of America’s First Serial Killer

Deranged: The Shocking True Story of America’s Most Fiendish Killer

Deviant: The Shocking True Story of Ed Gein, the Original “Psycho”

Fatal: The Poisonous Life of a Female Serial Killer

Fiend: The Shocking True Story of America’s Youngest Serial Killer

Psycho USA: Famous American Killers You Never Heard Of

Savage Pastimes: A Cultural History of Violent Entertainment

The Serial Killer Files: The Who, What, When, Where, How, and Why of the World’s Most Terrifying Murderers

The Whole Death Catalog: A Lively Guide to the Bitter End

NARRATIVE NONFICTION

The Devil’s Gentleman: Privilege, Poison, and the Trial

That Ushered In the Twentieth Century

Killer Colt: Murder, Disgrace, and the Making of an American Legend

FICTION

Nevermore

The Hum Bug

The Mask of Red Death

Outcry

The Tell-Tale Corpse

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, organizations, places, events and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

Text copyright © 2014 by Harold Schechter

All rights reserved.

No part of this work may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher.

Published by Amazon Publishing, Seattle

www.apub.com

Amazon and the Amazon logo are trademarks of Amazon.com, Inc. or its affiliates.

eISBN: 9781477850671

Cover design by Rodrigo Corral Design / Rachel Adam Rogers

Author photograph © Kimiko Hahn

Cover art © Superfly Images / Getty Images

In Memory of Harvey Shapiro

Contents

Cast of Characters

Prologue

Part I Beekman Place

1 Dead End

2 Vera and Fritz

3 “Beauty Slain in Bathtub”

4 Sex Fiends

Part II Fenelon

5 The Firebrand

6 The Brothers

7 Epiphany

8 Romanelli and Rady

Part III The Shadow of Madness

9 Depression

10 The Gedeons

11 Wertham

12 Bug in a Bottle

13 The Snake Woman

14 Canton

15 Crisis

Part IV The Mad Sculptor

16 Bloody Sunday

17 The Party Girl

18 Murder Sells

19 Prime Suspect

20 Manhunt

Part V The Defender

21 Murder in Times Square

22 Henrietta

23 The Front Page

24 Confession

25 Celebrities

26 Lunacy

27 Plea

28 Aftermath

Epilogue The Lonergan Case

Photos

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Cast of Characters

The Beekman Place Murders

VERA STRETZ, the “Skyscraper Slayer,” mistress and murderer of Fritz Gebhardt.

FRITZ GEBHARDT, prominent German industrialist with high political ambitions, Vera’s “Nazi Loverboy.”

NANCY TITTERTON, the “Bathtub Beauty,” editor, writer, murder victim.

LEWIS TITTERTON, Nancy’s husband, head of the script department of NBC radio.

JOHN FIORENZA, upholsterer’s assistant, Nancy’s killer.

The Artist and His Mentors

ROBERT IRWIN, the “Mad Sculptor,” artist, divinity student, mass killer.

CARLO ROMANELLI, renowned Hollywood sculptor, Robert Irwin’s first mentor.

LORADO TAFT, famed Chicago sculptor who took Irwin under his wing.

ANGUS MACLEAN, professor of religious history and future dean at the St. Lawrence University Theological School.

The Irwins

BENJAMIN HARDIN IRWIN, evangelist, founder of the Fire-Baptized Holiness Church, philanderer, father of the Mad Sculptor.

MARY IRWIN, Benjamin’s wife, religious fanatic, member of Florence Crawford’s Apostolic Faith Mission, mother of the Mad Sculptor.

VIDALIN IRWIN, older brother of Robert Irwin, juvenile delinquent, future inmate of Oregon State Penitentiary.

PEMBER IRWIN, younger brother of Robert Irwin, juvenile delinquent, also a future inmate of Oregon State Penitentiary.

The Gedeons

ETHEL GEDEON, older daughter of the Gedeon family, object of Bob’s amorous obsession.

VERONICA “RONNIE”GEDEON, party girl, artist’s model, murder victim.

JOSEPH GEDEON, Hungarian-born upholsterer, head of the Gedeon family, suspect in the “Easter Sunday Massacre.”

MARY GEDEON, Joe’s wife, speakeasy operator, landlady, murder victim.

JOE KUDNER, Ethel Gedeon’s second husband.

FRANK BYRNES, waiter at Manhattan’s Racquet and Tennis Club, boarded with the Gedeons, murder victim.

BOBBY FLOWER, briefly married to teenage Ronnie.

The Shrinks

FREDRIC WERTHAM, prominent New York psychiatrist who would treat and befriend Irwin.

CLARENCE LOW, president of the board of Rockland State Hospital and Bob’s patron.

DR. RUSSELL E. BLAISDELL, superintendent of the Rockwell State Hospital.

The Cops

FRANCIS KEAR, Deputy Chief Inspector, NYPD.

JOHN A. LYONS, Assistant Chief Inspector, NYPD.

ALEXANDER O. GETTLER, renowned “test tube sleuth” of the NYPD crime lab.

LEWIS VALENTINE, Commissioner, NYPD.

The Newsmen

WEST PETERSON, editor of Inside Detective magazine, offered one-thousand-dollar reward for help in Irwin’s arrest.

HARRY ROMANOFF, city editor of the Chicago Herald-Examiner.

JOHN DIENHART, managing editor of the Herald and Examiner.

The Good Samaritan

HENRIETTA KOSCIANSKI, Cleveland hotel pantry girl who recognized Bob from Inside Detective article.

The Suits

SAMUEL LEIBOWITZ, the “Great Defender,” lawyer for clients ranging from Al Capone to the Scottsboro Boys.

THOMAS DEWEY, Manhattan District Attorney, future governor of New York and Republican presidential candidate.

JACOB J. ROSENBLUM, Assistant District Attorney, Dewey’s right-hand man, assigned to try Robert Irwin.

PETER SABBATINO, lawyer hired by Ethel to represent Joseph Gedeon.

Prologue

268 EAST 52ND STREET, NEW YORK CITY

April 1937

From the window of his rented attic room, he can look across the low rooftop of the adjoining building and watch the hectic scene in front of the police station on 51st Street: the grim-faced detectives shoving their way through the clamorous mob of reporters, the squad cars delivering a steady stream of witnesses and suspects, the neighborhood gawkers jamming the sidewalks. On a couple of occasions, he spots the old man being hustl

ed in and out of the precinct house, doing his best to ignore the shouted questions of the newshounds.

By midweek, his meager provisions, the stuff he removed from their icebox, have run out. He will have to risk a trip outside for some food. Luckily, the scratches on his face have begun to fade. She had mauled him like nobody’s business. Put up a hell of a fight. Must have taken her twenty minutes to die.

He waits until nightfall, then slips downstairs and out the front door. After a hasty bite at an all-night cafeteria, he returns to his room with a sackful of groceries and the final editions of the Mirror, the Journal, and the News.

The papers are full of the story: “The Mystery of the Slain Artist’s Model,” “The Easter Sunday Murders,” “The Beekman Place Massacre.” Not one fails to mention its “curious parallels” to the Titterton killing during Holy Week a year before. Or to the Stretz case of 1935, also in the ritzy neighborhood of Beekman Place.1

He counts more than twenty photographs of Ronnie in the tabloids, most in cheesecake poses, her nakedness barely concealed by a gauzy, airbrushed veil. By contrast, he finds only a couple of Ethel, bundled in a fur coat, her face drawn, her frowning husband beside her. The grainy pictures do nothing to capture her perfection.

He is sorry to have caused Ethel grief. If she had been home that night, none of this would have happened. Otherwise, he feels not a twinge of remorse. Why should he? They aren’t really dead. Sure, they might be gone from this plane. But their lives aren’t lost. You can’t destroy one atom of matter. How are you going to destroy spirit?2

He reads about the growing list of suspects—Ronnie’s countless boyfriends, Mary’s former boarders, the Englishman’s shady acquaintances. Every cop in the city is on the lookout for the “mad slayer.” And all the while, he is right under their noses, holed up just a block away. He has made absolutely no effort to cover his tracks. Must have left dozens of fingerprints all over the apartment. Didn’t even bother to go back for the glove when he realized he’d left it behind. The incompetence of the police and their supposed scientific experts amuses him.

Still, he knows it is only a matter of time before his name comes up. By the end of the week, he decides to skip town. Someday, when he has made his great contribution to the human race, he will be able to travel just by visualization. Time and space will mean nothing. For now, he will have to rely on more prosaic means.

On Sunday, April 4, exactly one week after the Easter morning slaughter, Robert Irwin boards a train to Philadelphia.

Part I

Beekman Place

1

* * *

Dead End

BEEKMAN PLACE—A TRANQUIL East Side enclave just north of the United Nations and one of Manhattan’s most exclusive addresses—hasn’t always been home to the rich. Its name derives from the Beekman family, whose American branch dates back to 1647, when the wealthy Dutch merchant Wilhelmus Beekman arrived in the New World on the same ship carrying Peter Stuyvesant. In 1763, his descendant James Beekman built a stately country home on the high bank of the East River at what is now 51st Street. Furnished with costly imports and the handiwork of the finest colonial craftsmen, Mount Pleasant (as the picturesque white mansion was named) was commandeered by the British during the Revolutionary War and used as their military headquarters. The patriot-spy Nathan Hale was tried there for treason in September 1776 and held overnight in the greenhouse before being hanged the next morning in a nearby orchard. Following the war, George and Martha Washington are said to have paid frequent visits to Mount Pleasant, where “Mrs. Beekman would refresh them with lemonade made from fruit which she gathered from her famous lemon trees.”1

Abandoned by the Beekman family in 1854 when a cholera epidemic drove them from the city, the venerable mansion stood for another twenty years. By the time of its demolition in 1874, the once-bucolic area had been transformed into a stretch of stolid middle-class row houses, bordered by a shorefront wasteland of coal yards, breweries, and so many cattle pens, tanneries, and meatpacking plants that the neighborhood just to the south was known as Blood Alley.2 Following an evening stroll around Beekman Place in 1871, the diarist George Templeton Strong wryly noted its “nice outlook over the East River,” which included “a clear view of the penitentiary, the smallpox hospital, and the other palaces of Blackwell’s Island.”3

Over the following decades, the neighborhood continued to decline. As waves of European immigrants poured into the city and surged northward from the teeming ghettos of the Lower East Side, Beekman Place became engulfed by slums, its aging brownstones reduced to cheap boardinghouses for the foreign-born workers eking out a living at the waterside factories and abattoirs.

Its rehabilitation began in the 1920s when the East Side riverfront was colonized by Vanderbilts, Rockefellers, and other adventurous blue bloods. The old brownstones were renovated into stylish town houses, while several elegant apartment buildings, designed by some of the era’s leading architects, arose on the site. One of the most impressive structures was the twenty-six-story Art Deco skyscraper at the corner of East 49th Street and First Avenue. Intended as a club and dormitory for college sorority women, it was originally known as the Panhellenic House but was renamed the Beekman Tower when it became a residential hotel for both sexes in 1934.4 By then, the now-fashionable neighborhood was home to a particularly rich concentration of artists, writers, and theatrical celebrities, among them Katharine Cornell, Ethel Barrymore, and Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne. In later years, the neighborhood would boast such residents as Irving Berlin, Greta Garbo, and Noël Coward.

While Beekman Place and its even swankier neighbor, Sutton Place, were undergoing their revival, however, the surrounding streets remained untouched by gentrification. In the early 1930s, the area was a glaring study in contrasts, a neighborhood where luxury towers soared amid grimy tenements, where frayed laundry hung on lines within sight of private gardens, and where young toughs frolicked in the river beside the yachts and motor launches of the superrich.

In October 1935, New York theatergoers got a vivid look at this “strange otherworld” when the socially conscious crime drama Dead End opened on Broadway. Written by Pulitzer Prize–winner Sidney Kingsley (and later adapted for the screen by Lillian Hellman), the play concerns a poor aspiring young architect named Gimpty, hopelessly in love with a beautiful society girl; a vicious gangster named Baby-face Martin, drawn back to the old neighborhood by vestigial stirrings of human sentiment; and a gang of adolescent wharf rats seemingly doomed to criminal lives of their own. Its setting, inspired by the dock off 53rd Street just north of Beekman Place, is described in stage directions that perfectly capture the jarring contrasts that characterized the area in the mid-1930s:

DEAD END of a New York street, ending in a wharf over the East River. To the left is a high terrace and a white iron gate leading to the back of the exclusive East River Terrace Apartments. Hugging the terrace and filing up the street are a series of squalid tenement houses. And here on the shore, along the Fifties is a strange sight. Set plumb down in the midst of slums, antique warehouses, discarded breweries, slaughter houses, electrical works, gas tanks, loading cranes, coal-chutes, the very wealthy have begun to establish their city residence in huge, new, palatial apartments.

The East River Terrace is one of these. Looking up this street from the vantage of the River, we see only a small portion of the back terrace and a gate; but they are enough to suggest the towering magnificence of the whole structure.…Contrasting sharply with all this richness is the diseased street below, filthy, strewn with torn newspapers and garbage from the tenements. The tenement houses are close, dark and crumbling. They crowd each other. Where there are curtains in the windows, they are streaked and faded; where there are none, we see through to hideous, water stained, peeling wallpaper, and old broken-down furniture. The fire escapes are cluttered with gutted mattresses and quilts, old clothes, bread-boxes, milk bottles, a canary cage, an occasional potted plant struggling for life.5

Exactly two weeks after Dead End premiered, Beekman Place was suddenly in the news—not as the inspiration for Broadway’s latest hit but as the site of a shocking murder, a crime that swiftly turned into New York’s biggest tabloid sensation in years. Two other, even more gruesome killings would occur there within an eighteen-month span. One helped ignite a nationwide panic over a supposed epidemic of psychopathic sex crimes. The other came to be viewed as among the most spectacular American murder cases of the century.

If Dead End was meant to convey a message about the roots of criminality—“that mean streets breed gangsters”6—these grisly real-life crimes carried a moral of their own, one that had less to do with Kingsley’s brand of 1930s social realism than with the Gothic nightmares of Edgar Allan Poe. Beekman Place—a supposed bastion of safety for the privileged few—turned out to be much like Prince Prospero’s castellated fortress in “The Masque of the Red Death.” For all its wealth and glamour, it could not keep horror at bay.

2

* * *

Vera and Fritz

TO BECOME A TRUE TABLOID sensation, a murder has to offer more than morbid titillation. It needs a pair of outsized characters—diabolical villain and defenseless, preferably female, victim—a dramatic storyline, and the kind of lurid goings-on that speak to the secret dreams and dangerous desires of the public. In short, the same juicy ingredients we look for in any good potboiler.

Certainly there was no shortage of shocking homicides during the latter half of November 1935. In upstate New York, sixteen-year-old Sylvester Lancaric—resentful of the attentions his mother lavished on his baby brother, John—stomped his little sibling to death. Not many miles away, twenty-three-year-old LeRoy Smith of Ladentown was kidnapped, held captive for three days, then shot through the heart by the jealous ex-boyfriend of his teenage sweetheart, Mary Swope Philpot. A twenty-one-year-old Virginia woman, Edith Maxwell, killed her father by “beating him over the head with her high-heeled shoe when he attempted to whip her for staying out until nearly midnight” with her date. In Columbus, Texas, Benny Mitchell and Ernest Collins, both seventeen, brutally murdered nineteen-year-old Geraldine Kollman when she caught them stealing pecans on her father’s ranch. And in Washington, D.C., the body of twenty-six-year-old stenographer and choir singer Corinna Loring was found dumped in a park, her neck bound with wrapping cord and “wounds on her temple looking as though her head had been clamped in a pair of ice tongs.”1

The Mad Sculptor: The Maniac, the Model, and the Murder that Shook the Nation

The Mad Sculptor: The Maniac, the Model, and the Murder that Shook the Nation